Georges Simenon, Liège

From Flickr

Jules Verne, Vigo

From Flickr

René Descartes, La Haye-Descartes

From Flickr

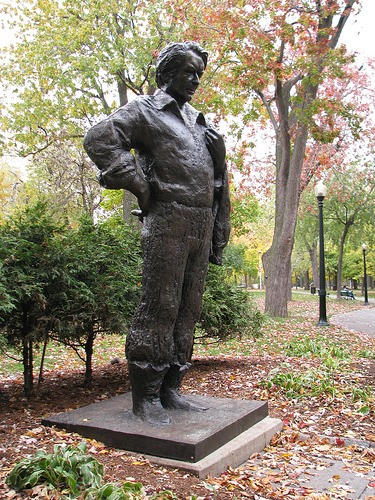

George Sand, Paris

From Flickr

Honoré de Balzac, Paris

From Flickr

Slogan localization draws on the full skill set and expertise required for transcreation, as well as the finely honed abilities of the copywriter.

There are a number of famous funny stories about translations of brand names and slogans that resulted in rather awkward situations.

In that respect, even big international corporations may run into trouble because of language and cultural subtleties.

For example, the name Coca-Cola in China was first rendered as Ke-Kou-Ke-La. Unfortunately, Coca-Cola did not discover, until after thousands of signs had been printed, that the sentence meant “Bite The Wax Tadpole” or “Female Horse Stuffed With Wax,” depending on the dialect; they then researched 40,000 Chinese characters and found a close phonetic equivalent, Ko-Kou-Ko-Le, which can be more or less translated as “Happiness In The Mouth.”

In Taiwan, the translation of the Pepsi slogan, “Come Alive With the Pepsi Generation,” came out as “Pepsi Will Bring Your Ancestors Back From The Dead.”

The American slogan for Salem cigarettes, “Salem—Feeling Free,” got translated in the Japanese market into “When Smoking Salem, You Feel So Refreshed That Your Mind Seems To Be Free And Empty.”

When General Motors introduced the Chevy Nova in South America, it was apparently unaware that “No Va” means “It Won’t Go.” After the company figured out why it was not selling any cars, it renamed the car in its Spanish markets to the Caribe.

Ford had a similar problem in Brazil when the Pinto flopped. The company found out that Pinto was Brazilian slang for “Tiny Male Genitals”. Ford pried all the nameplates off and substituted Corcel, which means horse.

When Parker Pen marketed a ballpoint pen in Mexico, its ads were supposed to say: “It Won’t Leak In Your Pocket And Embarrass You.” However, the company mistakenly thought the Spanish word “embarazar” meant embarrass. Instead, the ads said: “It Won’t Leak In Your Pocket And Make You Pregnant.” The Spanish word for “to embarrass” is “desconcertar.”

An American T-shirt maker in Miami printed shirts for the Spanish market which promoted the Pope’s visit. Instead of the desired “I Saw the Pope,” in Spanish, the shirts proclaimed “I Saw the Potato.”

Chicken man Frank Perdue’s slogan, “It Takes A Tough Man To Make A Tender Chicken,” got terribly mangled in another Spanish translation. A photo of Perdue with one of his birds appeared on billboards all over Mexico with a caption that explained, “It Takes A Hard Man To Make A Chicken Aroused.”

Hunt-Wesson introduced its Big John products in French Canada as Gros Jos before finding out that the phrase, in slang, means “Big Breasts.” In this case, however, the name problem did not have a noticeable effect on sales.

Colgate introduced a toothpaste in France called Cue, the name of a notorious porno mag.

In Italy, a campaign for Schweppes Tonic Water translated the name into Schweppes Toilet Water.

Japan’s second-largest tourist agency was mystified when it entered English-speaking markets and began receiving requests for unusual sex tours. Upon finding out why, the owners of Kinki Nippon Tourist Company changed its name.

In an effort to boost orange juice sales in predominantly continental breakfast eating England, a campaign was devised to extol the drink’s eye-opening, pick-me-up qualities. Hence the slogan, “Orange Juice. It Gets Your Pecker Up.”

Translating a slogan is a mere creativity job which requires a deep and thorough knowledge not only of the local culture, language and codes, but also of the local economics, politics and social life and players.